We are located at the edge of the Galactic disk, and see our Galaxy as a hazy band of light made of countless stars in the night sky. Looking for extragalactic objects like quasars through this band of light is so hard that this region has long been called the “Zone of Avoidance” for extragalactic astronomy. But now, a new research program makes it hard for quasars to hide themselves behind the Galactic plane.

An international research team led by astronomers from Peking University has identified 204 quasars behind the Galactic plane, 191 of which are new discoveries, using five optical telescopes in China, USA, and Australia. The new research, recently published in the Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series (ApJS), marks the successful lift-off of the spectroscopic observation campaign, after releasing the candidate catalog of quasars behind the Galactic plane with more than 160,000 sources previously selected by this team.

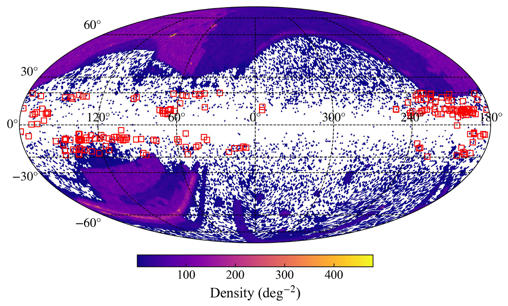

Figure 1. The sky distribution of the 204 identified quasars behind the Galactic plane (red squares) in Galactic coordinates. The density map of known quasars is shown in the background.

Quasars are luminous active galaxies with supermassive black holes at their centers, which releases huge amounts of energy through accreting surrounding materials. Quasars are probes of the distant universe and are keys to understand the formation and evolution of the supermassive black holes. Over the past few decades, great progress has been made in quasar surveys, yet the sky coverages of them are mainly limited to high Galactic latitude. By the end of 2021, nearly 830,000 quasars are found in the literature, while fewer than 6,000 of them (< 1%) are located in |b| < 20° (the Galactic plane; 34% of the entire sky), and fewer than 300 of them are located in |b| < 10°.

Despite the deficit of quasars behind the Galactic plane (GPQs), such quasars are of special interest to us due to their locations in the celestial sphere. “If we want to study the stars of the Milky Way disk, we need accurate measurements on their positions and motions from astrometric probes such as Gaia of the European Space Agency. To achieve that, astronomers use quasars to build the celestial reference frame, because quasars are so distant from us that they show almost no apparent motions on the sky,” said Yuming Fu, the first author of the new research, and a postdoctoral researcher from the Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics (KIAA) at Peking University.

“The Gaia mission has produced great data. However, we can barely determine the systematic errors of Gaia astrometry in the middle of the Galactic plane, just because we lack quasars there,” said Xue-Bing Wu, corresponding author of the new research and Professor from Department of Astronomy and KIAA at Peking University. “A large sample of GPQs is crucial to a better astrometric reference frame and a better understanding of the structures and kinematics of the Milky Way. Also, GPQs can probe the gas in the Galactic disk and provide a unique way of measuring Galactic extinctions.”

Finding GPQs is very difficult due to severe dust extinctions and reddening, as well as the crowded stellar fields in the Galactic plane. Existing selection methods for quasars developed using high Galactic latitude data cannot be applied to the Galactic plane directly, because the photometric data obtained from high Galactic latitude regions and the Galactic plane follow different probability distributions.

To alleviate such data set shift problem for quasar candidate selection, the research team led by Dr. Yuming Fu and Prof. Xue-Bing Wu has developed a transfer learning method for quasar selections, which reduces the difference of features(e.g. colors, magnitudes) between the training data and test data, and makes machine learning algorithm applicable to the classifications. To further remove stellar contaminants from the GPQ candidates, the team has also developed an additional method based on Gaia proper motions, which uses a cut on the “probability density of zero proper motion” to select quasar candidates. By applying these selection methods to the Galactic plane, they have obtained a reliable GPQ candidate catalog with 160,946 sources located at |b| ≤ 20° in Pan-STARRS-AllWISE footprint (Paper I).

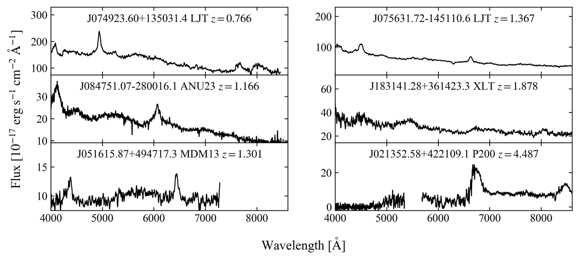

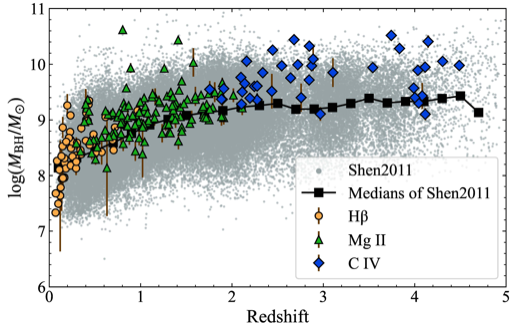

The team has been identifying GPQ candidates since 2018 with the 2.16 m Telescope (XLT; Xinglong, NAOC), the 2.4 m Telescope (LJT; Lijiang, YNAO), the 200 inch Hale Telescope (P200; Palomar), the ANU 2.3 m Telescope (ANU23; Siding Spring), and the McGraw-Hill 1.3 m Telescope (MDM13; MDM Observatory). Among 243 candidates that have been observed, 204 sources (84%) are successfully identified as quasars (see Figure 2 for a few examples). This new GPQ sample covers a wide redshift range from 0.069 to 4.487. In comparison to a genuine quasar sample from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS DR7Q), this GPQ sample has a higher average black hole mass, because intrinsically brighter quasars are more likely to be found in the Galactic plane (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Examples of the spectra of the 204 identified quasars behind the Galactic plane obtained with the five optical telescopes (XLT, LJT, P200, ANU23, MDM13).

Figure 3. Distributions of the black hole masses with redshift of the 204 GPQs, with yellow circles, green triangles, and blue diamonds showing black hole masses estimated with different emission lines. The black hole masses of SDSS DR7Q are shown as gray dots, and the median black hole masses of DR7Q in 24 redshift bins are shown as black squares.

The team expects to identify about 200 more new quasars at the very middle of the Galactic plane (|b| < 5°) in the next two years, and identify a few thousand GPQs at |b| ≤ 20° with the Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fiber Spectroscopic Telescope (LAMOST) Spectral Survey. The team members are also investigating the astrometric properties of the GPQs to assess the systematic errors of Gaia data in the Galactic plane. The GPQ project led by PKU astronomers extends the systematic searches for quasars to the dense stellar fields of the Galactic plane and shows the feasibility of using astronomical knowledge to improve data mining under complex conditions.

The new research (Paper II) has been published (Fu, Wu, et al. 2022, ApJS, 261, 32), following the publication of Paper I, which described the selection methods and candidate catalog of GPQs (Fu, Wu, et al. 2021, ApJS, 254, 6). The data that accompany the papers are available at the National Astronomical Data Center (NADC) of China.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation of China, and the science research grant from the China Manned Space Project. Candidate selections for the quasars were based on data from the Pan-STARRS survey, the AllWISE catalog, and Gaia Data Release 2. Spectroscopic observations were made possible with the Xinglong 2.16 m telescope, the Lijiang 2.4 m telescope, the Hale Telescope, the ANU 2.3 m telescope, and the MDM McGraw-Hill 1.3 m Telescope.

Links to the papers:

Paper I: https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4365/abe85e

Paper II: https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4365/ac7f3e

Links to the data:

Paper I: https://doi.org/10.12149/101052

Paper II: https://doi.org/10.12149/101140